My mother sent me this TedX video of David Autor, an MIT Professor of Economics. It's great. I highly recommend it. Here is his paper on the subject offering even more detail.

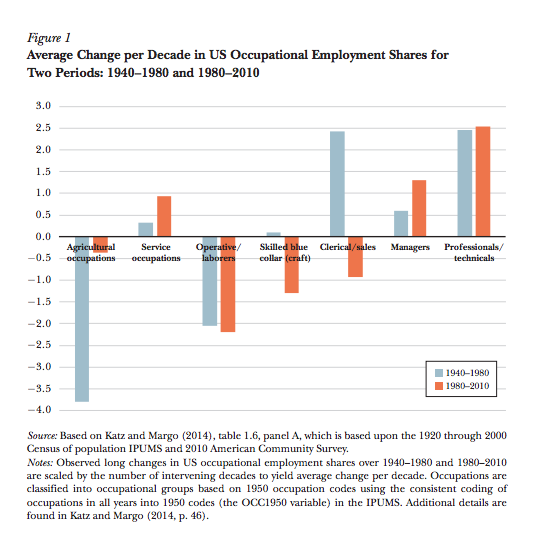

The impact of technology is all around us and just seems to accelerate leaving entire generations in lower-paid, less skilled jobs than they had only 30 years ago. This chart clearly shows waves of losses and gains in US employment by sector between 1940 and 2010.

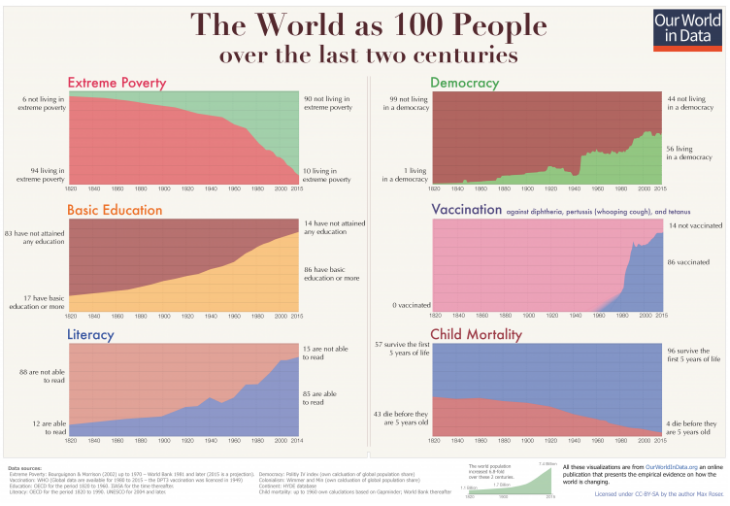

In fact, this is a paradox: an APPARENT (but not real) contradiction. Development overall shown in the chart above has not been bad for most of us. In fact, there is no real controversy here: although there have been real costs to some, most of us would recognize that we all have a higher standard of living and would agree that the benefits to all of us far outweigh the costs.

How does this actually work? Why hasn't it been a zero sum game where the machines take over, at least not until now?

Autor, a professional economist, does an excellent job explaining how this is possible. He begins by recognizing the virtuous cycle of technological development and labor in a market economy. First, the more we invest in technology the more productive we are as an economy. He's looking at labor in the aggregate. Greater wealth stimulates demand. Displaced labor finds even more valuable employment opportunities, acquires new skills, earns more and then demands even more goods and services. Growth spawns more automation. It's all good.

But Autor also concedes there is a challenge: unless we apply the wealth generated by automation to our institutions, to our society, and to ourselves, the virtuous cycle will end. Although he does not even mention inequality in his TED talk, his written work does acknowledge that it might be severe enough to limit broad-based consumer demand, breaking the cycle. Again, there is no controversy here. Our academic, political and business leaders agree that these risks are real, even if we disagree on how likely they are or how severe they might become.

I would break his argument down into four basic parts:

- Automation makes human labor MORE valuable: the 'O-ring' effect

- Productivity creates wealth that spawns new demand: we can't get enough

- Human ingenuity has always saved us in the past: this time is NOT different

- He's telling us something new, something we have not heard elsewhere

Let's critically examine each of these in turn.

First, overall, automation HELPS human workers be more productive, it does not replace them. The 'O-ring' is a metaphor for the value of even the least expensive critical part in a complex system: the more reliable the rest of the system becomes, the more value there is in every critical component. Of course he's right: SOME of the remaining jobs are indeed even more critical to the system as a whole and become more valuable. For example, there are more bank tellers now than there were before the advent of ATM's and, overall, they are paid more and offer more complicated, more valuable kinds of customer service than their robotic 'assistants'.

On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence to the contrary that suggests that MOST of the remaining jobs are, in fact, less critical to the overall systems performance and productivity and are therefore generating less value. Sure, there are some good jobs at Amazon, but they aren't nearly as numerous as the retail jobs they have displaced. Even though Walmart has grown, retail sales in that context no longer require or pay for the skills it once did. So these effects reducing the value of human labor are also real, offsetting the gains in other jobs. I would love to see these kind of labor statistics across the entire planet, the only way to study the effects of automation in a global economy where immigration and globalization negatively impact earnings in addition to automation. But I've not seen those studies. Even without the hard data, I think we can agree that both automation and globalization play a role and that reality is more complex than Autor would have us believe with his 'O-ring' argument.

And so far, there is no news here. These are old, old stories that are not as controversial as Autor suggests.

Let's consider the argument that productivity creates wealth that raises our standard of living and in turn spawns demand. Does it? Well, of course there are no limits to what humans want. However, if we need money from our labor to fulfill those desires and we're limited by how much our labor is worth, there ARE LIMITS to how much demand can be expressed in consumer markets.

As Autor says, "It depends on what we DO with the wealth." If most of that is captured by the the top 1% and saved, well, it simply does not stimulate demand and growth. Even if we invest in institutions like education as we have in the past, what jobs would we be training our displaced workers for precisely? It's not clear. There is plenty of evidence that that wealth is indeed being invested. It must go somewhere. But without demand, all that capital is being applied to stock buybacks and acquisitions, not growth and not new jobs. It seems to me that we have a surplus of capital and capacity which is consistent with disappointing growth in high quality jobs.

As Autor says, "It depends on what we DO with the wealth." If most of that is captured by the the top 1% and saved, well, it simply does not stimulate demand and growth. Even if we invest in institutions like education as we have in the past, what jobs would we be training our displaced workers for precisely? It's not clear. There is plenty of evidence that that wealth is indeed being invested. It must go somewhere. But without demand, all that capital is being applied to stock buybacks and acquisitions, not growth and not new jobs. It seems to me that we have a surplus of capital and capacity which is consistent with disappointing growth in high quality jobs.

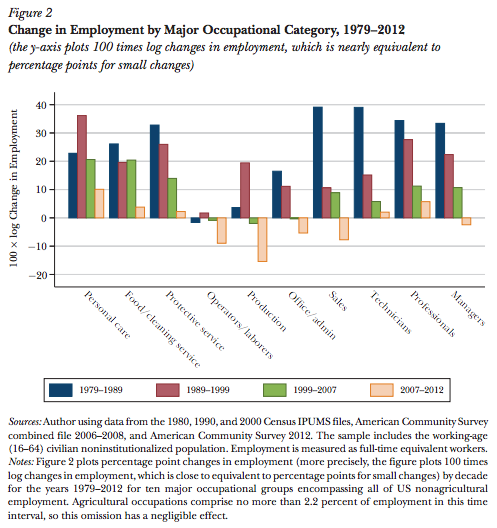

Look at the reduction in what we would consider "middle income" jobs:

He looks at this data and sees the glass half full. I look at it and worry, not just about the jobs themselves but about how this affects the distribution of income and the engine that drives demand and growth.

What we have instead of broad-based participation in the automation economy is what Autor calls "income polarization," another name for inequality:

Again, no real news. In his TED talk, Autor makes an oversimplified argument which is true... but incomplete. Why not concede that there are also mitigating factors that diminish the effect of productivity gains, specifically increased inequality?

Finally, what about human ingenuity? Perhaps I am unimaginative and perhaps we WILL be saved. I just don't think so because this time IS different. Of course, every time this has happened in the past it HAS ALSO been different. But we need to pay attention to WHY SPECIFICALLY this time is different and look for differences that might affect the balance of displaced jobs and income inequality I describe above.

Consider:

- Until now, the vast reservoir of new work that has absorbed displaced labor has been COGNITIVE work.

- Until now, the growth in COGNITIVE labor has increased the wealth of the middle classes which has also increased DEMAND.

- This time the machines are COGNITIVE machines.

- This time the machines are NETWORKED, creating essentially a singular, global machine.

- Digital communications are essentially free, connecting everyone on the planet to the global machine. This time there are fewer essential human ‘O’ rings. This time there are even fewer owners reaping the rewards of automation.

- This time, more displaced workers will make LESS income, not more, REDUCING DEMAND.

Ultimately, it’s true that we “can’t get enough.” Unfortunately, that unlimited demand is only expressed in markets when those people have money. And increasingly, it’s only the people who are making the machines and ultimately OWN shares in the machines who are collecting all the money. Everyone else is UNDEREMPLOYED but working harder than ever. That means they are earning and consuming less. This leads to a crisis in DEMAND. Which leads to slow or negative growth. See Robert Reich's "Inequality for All" if you haven't already; it's fabulous.

But as Autor says, this is not PREDETERMINED. We can choose to redistribute wealth in new ways to prevent the worst inequality, to share more widely the benefits of automation, to enable more people to work less. By sharing more, by allowing more people to participate in the automation economy, we might even stimulate demand while we elevate our standard of living.

But will we?

6 comments:

Our illustrious President-Elect and his party of goons have a different plan, unfortunately - not that any of their measures will succeed, but we will be subjected to the attempt (encourage use of fossil fuels, bring back jobs that rely on old technology by protecting them under tariffs, lower taxes to stimulate the economy and generate jobs, etc.!) Meanwhile actual solutions (make educatiin and training less expensive to prepare people for more highly leveraged intelligence- intensive work), increase taxes on those who benefit most from the current economy to maintain and upgrade infrastducture to support clean energy, communication, transport, etc.) And so it goes.

Thanks, Rich. And so it goes.

I like to think that Trump (and Sanders and Warren and even Clinton, to some extent) have all identified aspects of a very real problem. Perhaps the American Dream was never quite as real or quite as widely experienced as we told ourselves. Perhaps the 50's and 60's were a total anomaly in the history of the world where virtually everyone in each successive generation actually believed they would earn more (and consume more) than their parents. But the perception now, supported by 40 years of diminished real wages for all but the highest earners, is that we're moving in the wrong direction. Now we have downward mobility.

None of our most visible leaders are really offering solutions, in my opinion. No one is telling us the truth about how hard this is going to be, preparing us for the work we need to do. But Trump is clearly lying about the problem, blaming it on immigrants (which is NOT true) and trade (which may be partially true). And, perhaps even more importantly, he's lying about what he's going to DO about it. His non-existent policies and ideologically-pure-but not-so-competent Cabinet is only going to accelerate the process while further divesting in our institutions, the public sector, and our common social, political and economic infrastructure.

Meanwhile, by tapping into the real anger that's out there for electoral success and promising things he can never deliver, he's playing with fire. In a society where your value as a human being is connected on a fundamental level to how much you earn and what you do for a living, we don't just have a material problem with "lifestyle" but a much more serious and difficult problem with human dignity. Unfortunately, and I would add understandably, there is a lot of anger out there.

And so it goes.

Thanks for putting together your thoughts on this, Steve! I just shared a link to this post on LinkedIn where I'm connected to a variety of people interested in the future of work.

Now that I have a keyboard at my disposal, I'd like to respond more fully:

I tend to think that to say Trump "identified aspects of a very real problem" is to give him far too much credit. I think it would be more accurate to say that given his long, disgraceful public record, he has more likely *exploited* a very real problem. I suppose only his tenure as president will bear out which of us is more on target.

I think that to some extent a decline from the political and financial peak enjoyed by Americans in the 50s and 60s was inevitable. After all, we were the only major power left at the end of WWII with its industrial base unscathed. In fact if anything, war production jump started our economy and it converted to peace time production without missing a beat. Unfortunately in the post-war period American industry and those who participated in it grew insular, fat and self-satisfied. Meanwhile by the 70s Americans in general seemed to have forgotten who paid for most of the basic research that led to America's technological superiority. Hint: it was NOT the 1%. I think that repeatedly electing a party to national office whose creed is that "government is the problem" is to deny the critical role that the US government has played as independent arbiter in maintaining a level economic playing field (e.g., anti-trust laws that were put in place in the late 1800s, quality public education that achieved near 100% literacy in a generation, rural electrification, resolving the "dust bowl" disaster, turning back the Great Depression while upgrading the entire nation's infrastructure, basic research that helped win WWII and enabled humankind to reach the Moon, and technological spinoffs from the space program and military that kindled a revolution in electronics, computers, medicine, material science, etc.) Federal spending and policies were the catalyst for all these developments and more.

Yes, there is a lot of anger. Two year olds are also known for their tantrums - and so is Trump for his Tweet storms. The angry minority (Let us not forget that they missed being a majority by 3 million votes - should the majority who voted for someone else not be feeling any anger?) elected a man who is very much like themselves temperamentally. As someone who sprouted from a working class background, I can tell you that most of the people around me thought of themselves as trapped. Sadly, they were - and are - trapped by their own thinking (or lack thereof). I don't know how they came to believe that anything good would flow from following the program laid out for them. The people I know rarely attempt much of any truly independent or rigorous thought. They prefer to choose life from a menu, to paint by numbers. They can't be bothered with digging for primary sources, or dispelling their misconceptions, naive theories or simplistic explanations. There is in principal not much difference between them and the mob that condemned Socrates. To the extent their political will is expressed in electing a "leader" like Trump, they are the Achilles heel of the body politic. That there are angry people who feel trapped in the first place is largely the result of Republican policies which since 1980 have favored corporate interests over "Main Street" interests, deregulated Wall Street, de-funded public education, de-funded NASA, de-funded basic research, cultivated the denial of climate science and discredited the pursuit of science in general, pursued foolish and empirically unfounded economic policies, and so much more. And now they have run the table. Oh, joy!

Thanks, Rich.

I agree with your take on Autor's presentation. This time IS different for exactly the reasons you cite. Economic demand IS what drives the economy, and that demand is generated by spending money in the average person's pocket, not by any increase in investment capital. Of course capital is necessary - but the amount of capital available has *never* been greater, while the strength of market demand is relatively anemic, and not increasing fast enough to dispel worries. The recent protracted period of low interest rates should be enough to convince any skeptic. And now, even as unemployment has been driven to its "full employment" low benchmark, there is little upward pressure on wages. Just as the Fed has been bouncing on the bottom with little ammunition left to stimulate the economy, full employment which would normally produce upward pressure on wages seems to be having little effect. The economy does seem to be caught in the doldrums - even when experience predicts it should be taking off. This has to be caused by the market's placing lower value on the work performed by the majority. As you rightly point out, leveraging human labor this time is more difficult than in the past now that machines can perform so well - at everything, including many high-value tasks that were once the sole domain of human labor. Making matters worse, income disparity over the past 30 years has increased far beyond what it was during its previous peak a hundred years ago, and most wealth is now inherited by successive generations, practically guaranteeing that most of the capital will remain concentrated in the hands of the few, and that incomes are unlikely to balance out. We now have the 1% with practically limitless power economically and politically, and we have everyone else. I think that anyone who expects redistribution to save us is a bit naive. Redistribution has become a dirty word in today's America, as have many political ideas once thought to be mainstream. In their place we have good old fashioned American conservatism, the same folks who sell the idea that cutting taxes on the wealthy will solve everyone's problems. They currently have what is probably the most bulletproof majority the House of Representatives has ever seen. And that is where laws originate. They have bulletproof majorities in the majority of state houses as well. They have both a well established propaganda machine and a willing populace at their disposal. They are about to have a solid majority on the Supreme Court. And of course, they have their own pet loose cannon in the White House. I don't see any solutions looming on the horizon, unfortunately... If by some miracle we (the Federal government) were able to fund massive increases in education and training programs and invest in infrastructure, there *might* be some uptick in wages as a result in the increase in demand for labor (since infrastructure improvement and education have not yet been automated). I don't believe we will be seeing anything like this anytime soon. If there were some attention focused on the current distribution of wealth and some recognition of the ill effects of this on economy and government alike, maybe some solution could be found? If there were more attention focused on the climate change problem, maybe some new enterprises and well-paying work for humans might be one result? But until some authority (all of us, in the form of the body politic) imposes some rules and regulations to address this, there will be no level playing field and individual corporations will do what they must to remain competitive. No company is able to make the first move until someone levels the playing field by imposing regulations.

Post a Comment